Who knew that a trip to a garden would make a rock fan of me, but that’s exactly what happened on a recent visit to the National Botanic Gardens of Wales in Carmarthenshire!

On a dreary and damp day in mid May when even the flowers and plants were looking depressed, my spirits were lifted when I came across a pathway meandering through a timeline spanning over 300 million years of Welsh geology, displaying rocks and their history from across the whole of Wales. Eager to find out more, I was intrigued to learn that far from being dead and lifeless, the rocks around us are full of energy and life, sustaining various specialised plants, mosses and in particular, lichens.

More than 75 species colonise these rocks, and for countless years they have been used in many diverse ways. For instance, the lichen known as crottle (Parmelia saxatalis – pictured above) gives a red dye used in the production of Harris Tweed, and in medieval times this same lichen was considered to be a cure for epilepsy, but only when harvested from bones – apparently that taken from the skull of a hanged man was the most prized! The slow growing crusty lichen Buella aethalea has growth rings making it valuable for dating rocks, and its size has been used for estimating the date of ancient tsunamis and the retreat of glaciers.

The relatively new science of geology began in Britain during the 18th century, born of the Industrial Revolution and the construction of the canals. The resulting excavations exposed many different rocks, each with their own distinct fossils reflecting a range of climatic conditions, ranging from extreme cold through to tropical. This is because at the start of the Cambrian Age the landmass which would eventually become England and Wales was situated at the South Pole, moving north-west over a period of 550 million years to eventually collide into Scotland and Ireland some 400 million years ago, having crossed the Equator on the way.

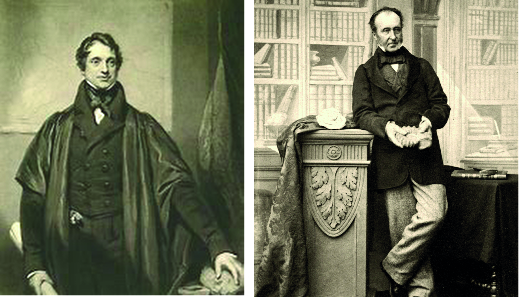

Adam Sedgwick (left) and Roderick Murchison

Wales has a particularly complex and varied geology, and as such its study has played a major role in the development of this science.

Leading geologist of the day, Adam Sedgwick, named the Cambrian period after studying rocks in the Snowdonia area of Wales, while Roderick Murchison, who studied the younger rocks of the Welsh borderlands named these the Silurian Formation after ancient Welsh tribe, the Silures. The two men were fierce rivals, and they hotly debated the boundary between the Cambrian and Silurian for decades. Following their death, geologist Charles Lapworth suggested that the upper Cambrian rocks of Sedgwick and the lower Silurian rocks of Murchison were in actual fact the same, and in 1879 he put forward the name Ordovician to describe this formation, referencing another Welsh tribe, the Ordovices.

Ever since, these names have been used by geologists across the world and over 90% of the geological stages in the history of the planet are named after Wales, or Welsh tribes.

Ironically, it took this visit to South Wales for me to learn more about the Carboniferous Limestone of my home patch in North East Wales. Two different types of this limestone are quarried from both the Pant and Pant-y-Pwll-Dwr quarries in Pentre Halkyn, just a couple of miles from my home in Cilcain. One is very muddy and full of fossilised shells, and the other, quarried further down the hill, is smooth and pale grey in colour, and many buildings and walls in the surrounding area (including my house!) are built from this stone.

Carboniferous limestone at the National Botanic Gardens of Wales, quarried from Pentre Halkyn in Flintshire

Limestone is dissolved by the action of acid water and lichens, which over long periods of time helps to form a lime-rich soil, valuable as pastureland.

The limestone of Denbigh in North East Wales provides a home for one of Britain’s rarest wildflowers, the Limestone Woundwort (Stachys alpina), which is also the county flower of Denbighshire – Gloucestershire is the only other place this plant can be found growing in the UK. Locally, attempts have been made to conserve it by sowing seed and by rotovating bare patches of soil to disturb seed which may be lying dormant.

Massive tectonic shifts, volcanoes and glaciers have all helped to shape the beautiful country of Wales, with its rolling hills, soaring mountains, and deep, silent lakes. Through the exploitation of its mineral wealth, the diverse geology of this country has provided employment and prosperity for hundreds of years, from the red fire of the coal which powered the Industrial Revolution, the slate which has famously roofed the world, hard-won from Snowdonia, to the rare and precious glint of Welsh gold on the fingers of royalty to this day.

Cover photograph courtesy of Lukas Hartmann

Really fascinating, Sonia. xx

Thank you, Gwen – glad you enjoyed it!

Thank you, Agnes. I thoroughly enjoyed my research into the rocks and geology of Wales.

I would like to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this blog. I’m hoping to check out the same high-grade content by you later on as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has inspired me to get my very own website now 😉

Thank you so much for your kind remarks, really brightened up a rather dull day! Good luck with your website, and please let me know when it’s up and running so I can take a look 🙂